Even before our primate ancestors began to walk upright, there were wars—times when whole human communities or groups within a community tried to kill each other. Scholars have reached this conclusion partly on the basis of Jane Goodall’s discovery that our closest primate relative, the chimpanzee, engages in war,(1) and partly on the basis of archaeological evidence. One site of skeletons was found in Kenya dating back 9,500 to 10,500 years showing that a group of 27 people had been massacred together.(2) Indeed, there is strong evidence that levels of violence were higher in prehistoric times than today.(3) One example is a cemetery about 14,000 years old where about 45 percent of the skeletons showed signs of violent death.(4) An estimated 15 percent of deaths in primitive societies were caused by warfare.

But life did not consistently become friendlier as our species spread and developed. By one estimate, there were 14,500 wars between 3500 BC and the late twentieth century. These took around 3.5 billion lives.(5)

Can we conclude, then, that war is simply an intrinsic part of “human nature,” so that one cannot reasonably hope to overcome it? No, for there is more variation in the frequency and extent of warfare than can be attributed to genetic differences. In some societies, war is completely absent. Douglas Fry, checking the ethnographic records, identified 74 societies that have clearly been non-warring; some even lacked a word for “war.” The Semai of Malaysia and the Mardu of Australia are examples.(6)

We may gain insights about solutions to warfare by exploring the variations in its distribution, type, and intensity. We begin with the best news: We are probably living in the most peaceful period in human history!

Steven Pinker is the scholar who most convincingly argues that violence has declined, both recently and over the millennia. Pinker’s book Enlightenment Now, contains a graph showing the numbers of battle deaths by year from 1945 to 2015. A huge spike represents World War II, of course, for that was most lethal war in human history, causing at least 55 million deaths. How can we reconcile that ghastly number with any claim that the modern era is a peaceful epoch?

Pinker’s proof is based on distinguishing sharply between absolute numbers and rates. To be sure, 55 million is a huge number, but the Mongol Conquests killed 40 million people back in the thirteenth century, out of a world population only about one-seventh the size of the world’s 1950 population. Pinker says that if World War II had matched the Mongols’ stupendous rate of killing, about 278 million people would have been killed.

And there was an even worse war than the Mongol Conquest: the An Lushan Revolt of eighth century China, an eight-year rebellion that resulted in the loss of 36 million people — two-thirds of the empire’s population, and a sixth of the world’s population at the time. Had it matched that level of atrocity, considering the size of the world’s population in the 1940s, World War II would have killed 419 million people! Pinker calls An Lushan the worst war in human history. By his calculations, based on rates or percentages, World War II was only the ninth worst in history and World War I was the 16th worst.(7)

Moreover, Pinker shows that the two world wars were huge spikes in a graph of war deaths that has declined remarkably since 1950. There has been a slight upward bump since 2010, representing the civil war in Syria, but even that increase is minuscule in comparison to the rates of battle deaths over the preceding centuries.(8)

Pinker admits that there is no guarantee that this civilizing trend will continue, but he marshals much empirical evidence to explain it in terms of several historical changes. One was the transition to agriculture from hunting and gathering. This brought about a fivefold decrease in rates of violent death from chronic raiding and feuding.(9)

A second factor occurred in Europe between the Middle Ages and the 20th century when feudal territories were consolidated into large kingdoms with centralized authority and an infrastructure of commerce. This led to a tenfold-to-fiftyfold decline in homicide rates. There have been numerous other changes since then, including the abolition of such practices as slavery, dueling, sadistic punishment, and cruelty to animals. Since the end of World War II the downward trend has been remarkable.(10)

Nature

Unlike Steven Pinker, who attributes the current relatively wonderful degree of peacefulness to cultural and social changes in history, Dave Grossman attributes it to nature itself. In contrast to those who claim that human nature destines us to be killers, Grossman argues that people are “naturally” reluctant to kill members of their own species. In this respect we resemble other animals, for it is normal for animals to avoid killing their own species. When, for example, two male moose bash each other with their horns, they rarely do much real damage.

In fact, the human reluctance to kill their own kind poses a real problem for military leaders, who must induce their soldiers to fight wars. Lt. Col. Grossman himself had been responsible for training US Army Rangers, and he seems to have taken considerable pride in overcoming nature’s inhibitions.

Grossman cites Brigadier General S. L. A. Marshall’s book Men Against Fire, which showed that only 15 to 20 percent of the individual riflemen in World War II fired their weapons at an exposed enemy soldier.(11) Similar results can be shown in earlier wars as well, including for example the battlefield of Gettysburg, where of the discarded muskets later found there, 90 percent were still loaded.(12)

On the other hand, soldiers who work together as crews (e.g. in launching cannon-fire or flamethrowers together) do not show the same hesitation, nor do soldiers whose officers stand nearby, ordering them to fire. And distance matters too; stabbing an enemy is harder to do than shooting one a few meters away, and the farther away the enemy is, the easier it is to shoot him. Bombardiers rarely hesitate to drop shells on the people below, nor do drone operators sitting at controls in a different continent. Distance, team spirit and authority can apparently overcome nature’s misgivings.

In response to Marshall’s discovery, the U.S. military developed new training measures to break down this resistance. For example, instead of having soldiers fire at bulls-eye targets, the army now provides realistic human-shaped silhouettes that pop up suddenly and must be shot quickly. The training also relies on repetition; soldiers are required to shoot many, many times so they stop thinking about the possible implications of each shot.(13)

The best technological innovation for inuring fighters for battle is the video training simulator. As a result of using the equivalent to violent videogames, the military successfully raised soldiers’ firing rates to over 90 percent during the Vietnam War. Because of this “superior training,” Grossman claims that today “non-firers” are almost non-existent among U.S. troops.

While lauding the military for developing such excellent training systems, Grossman is scathing in criticizing the use of video games as entertainment. He maintains that the very methods that turn soldiers into superb killers will, and do, influence the players to become violent in real life. He blames the epidemic of school shootings, for example, largely on the exposure of teen-aged boys to violent films and especially violent video games.(14)

Moreover, the training of soldiers for battle does not protect them from the psychological consequences of fighting. In a study of World War II soldiers, after sixty days of continuous combat, 98 percent of all those surviving had become psychiatric casualties. One-tenth of all American military men were hospitalized for mental disturbances between 1942 and 1945.[14] Moreover, upon their return to civilian life, the incidence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder remains high, and more veterans commit suicide than had been killed during the war. Also, the U.S. Army dismissed more than 22,000 soldiers for misconduct between 2009- 2016 after they returned from war with mental health problems or brain injuries.(15)

These facts clearly disprove the assertion that human nature itself destines us all to be killers; indeed, one might argue that, on the contrary, nature intends for us all to be peaceful. However, even that assertion is hard to sustain when we look at the evidence showing how widespread is the cultural pattern of glorifying war and warriors.

The Hero Warrior

Not everyone is reluctant to kill. On the contrary. For example, consider Mr. L, an Asian friend of ours whose brother was found decapitated on a forest trail. Mr. L knew who had done it — the army of Burma — so he went to the jungle and joined the resistance army. For seventeen years he was a sniper. Now living in Canada, he finds the memory hard to explain:

“Actually, I loved it. I probably killed about thirty men in all, and it was the greatest feeling! I was always so elated after killing an enemy soldier that I couldn’t sleep that night. That’s what I went to there to do, after all. But now? Well…”

No one in Canada glorifies Mr. L’s achievements, but in another time or place he might be considered a war hero. Brave, effective warriors have been honored by their own societies at least as far back as the ancient Assyrians and Greeks.

There were good reasons for it. When our ancestors still lived in caves, presumably some strong fellow volunteered to stand guard at night to keep out the saber-toothed tigers. His mother must have felt proud of him, and perhaps also praised him and his brave buddies for raiding the neighbors’ cave and bringing home valuable loot.

The Iliad is one long bloodcurdling story about heroes seeking to outdo each other in courage and brutality. Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values.(16) Among the most intelligent militarists who glorified war was the philosopher Georg Hegel,(17) whose views were perfectly ordinary in the Prussian society of his day.

A century later in America militarism was not quite as popular, but the great American psychologist William James, who was a pacifist, could nevertheless understand and even respect it as a moral stance. He pointed out that young males need a thrilling opportunity to test their capacity for enduring physical hardship and surmounting obstacles. That is what sports are for, but James wanted this experience to involve sacrifice and a sense of service as well. He was seeking to innovate a rigorous substitute for military discipline whereby youths could instead contribute positively to society. James understood the emotional value and even romance of militarism, as shown in his sardonic depiction of war from the militarists’ point of view:

“Its ‘horrors’ are a cheap price to pay for rescue from the only alternative supposed, of a world of clerks and teachers, of co-education and zoophily, of ‘consumer’s leagues’ and ‘associated charities,’ of industrialism unlimited, and feminism unabashed. No scorn, no hardness, no valor any more! Fie upon such a cattleyard of a planet!”(18)

James believed that this “manly” yearning for hard challenges ought to be fulfilled. He proposed a system of national service whereby all young males would be conscripted to serve in a challenging role. (He called it a “war against nature,” which is a shocking notion today; we’d prefer to call it a “war for nature.”) He thought that privileged youths should have to experience at least once the hardships that poor people endure throughout their lives. And indeed, since James’s day, the United States and many other prosperous societies have developed programs such as the Peace Corps to fill that need. It is unlikely, however, that the challenges they offer overseas are comparable to the emotions of killing or stepping onto a landmine.

If Pinker’s fond hopes (and our own) could be fulfilled, the planet might indeed resemble what James’s militarists consider a boring “cattleyard” — but that seems unlikely to occur. Our war heroes are still celebrities. And many of them still commit suicide.

The Evolution or the Death of Warfare?

Pinker’s statistics are correct, but it is far too early to celebrate the impending death of war. Weaponry continues to become ever more deadly, and the history of warfare is best described in terms of the evolutionary improvement of weapons. We present in Table 1 the summary of those developments provided by Dave Grossman and Loren Christensen— who, oddly, have omitted today’s worst weapons of mass destruction, as well as the future of autonomous weapons and cyber weapons. These innovations require our utmost concern.

Table 1. Landmarks in the Evolution of Combat

Dates generally represent century or decade of first major, large-scale introduction

c. 1700BC Chariots provide key form of mobility advantage in ancient warfare

c. 400BC: Greek phalanx

c. 100BC: Roman system (pilum, swords, training, professional leadership)

c. 900AD: Mounted knight (stirrup greatly enhances utility of mounted warfare)

c. 1300: Gunpowder (cannon) in warfare

c. 1300: Wide scale application of long bow defeats mounted knights

c. 1600: Gunpowder (small arms) in warfare, defeats all body armor

c. 1800: Shrapnel (exploding artillery shells), ultimately creates renewed need for helmets, c. 1915

c. 1850: Percussion caps permit all-weather use of small arms *

c. 1870: Breech-loading, cartridge firing rifles and pistols

c. 1915: Machine gun

c. 1915: Gas warfare

c. 1915: Tanks

c. 1915: Aircraft *

c. 1915: Self-loading (automatic) rifles and pistols

c. 1940: Strategic bombing of population centers

c. 1945: Nuclear weapons

c. 1960: Large scale introduction of operant conditioning in training to enable killing *

c. 1960: Large scale introduction of media violence begins to enable domestic violent crime

c. 1965: Large scale introduction of helicopters in battle

c. 1970: Introduction of precision-guided munitions in warfare

c. 1980: Kevlar body armor provides first individual armor to defeat state-of-the-art small arms in over 300 years *

c. 1990: Large scale introduction of operant conditioning through violent video games begins to enable mass murders in domestic violent crime

c. 1990: First extensive use of precision guided munitions in warfare (approximately 10 percent of all bombs dropped), by Unites States forces in the Gulf War

c. 1990: Large scale use of combat stress inoculation in law enforcement, with the introduction of paint bullet training

c. 2000: Approximately 70 percent of all bombs used by United States forces in conquest of Afghanistan and Iraq are precision-guided munitions

c. 2000: Large scale use of combat stress inoculation in United States military forces, with the introduction of paint bullet combat simulation training *

* Represents developments influencing domestic violent crime.

Source: Grossman and Christensen, Evolution of Weaponry. Loc. 2058 in Kindle version

In a nutshell, weapons keep get more and more effective at killing, and the population keeps increasing (especially during the past century), so this might suggest a gloomy prediction: that we must expect a world war vastly larger than either of the two previous ones.

But neither Pinker nor Grossman have concluded that the magnitude of a war will inevitably be determined by either the population or the effectiveness of weapons. Pinker believes that the records of history show that war is rather randomly distributed over time and space, not following any discernable pattern.

Scholars know quite a lot about warfare in early civilizations, for we have epic stories such as Gilgamesh in Mesopotamia (about 2500 BCE) and Achilles versus Hector in Homer’s Greece (supposedly 1184 BCE).

The Hittites invented the chariot, and the Egyptians adopted it from them, though there were long intervals when chariots were not used in any Middle Eastern wars. Though the Greeks often used chariots, they would sometimes stop and dismount for hand-to-hand combat. The Greeks invented the phalanx, or row of middle-class citizen-soldiers(19) fighting side by side with their shields overlapping, with long pikes against an enemy’s phalanx.

But the elite warriors worked differently. Achilles, for example, would individually single out the enemy he considered a worthy match. Such a noble warrior might stroll across the battlefield to the enemy’s side, and call out their best fighter by name to come and fight him to the death. This kind of semi-organized warfare also has been practiced until recently in some paleolithic societies, such as in Papua New Guinea.(20)

We need not trace the complete evolution of weaponry from ancient times to now, except to mention a few dramatic innovations. One was the invention of gunpowder, which of course made it easy to kill large numbers of opponents. It was discovered in China during the late ninth century, but was not used in that country except for fireworks. It was adopted in the West, and ironically, much later, the Chinese were defeated by Westerners with firearms.

Historians debate why the Chinese did not use gunpowder(21) for military purposes, but the more interesting point is simply the fact that they did not. We can take this as evidence that technological innovation does not take an inevitable course, for sometimes a society opts not to perfect a weapon that offers the every prospect of improved effectiveness.

Much later, there were other extraordinary military discoveries that have been prohibited almost everywhere. Chemical weapons (notably chlorine, phosgene, and mustard gas.) were used in World War I. Although the Germans soon developed powerful nerve agents such as sarin, no chemical weapons were used in World War II. Some say that Hitler ruled out using them against troops because he had experienced gas poisoning during World War I. However, he did not hesitate to use them in his death camps. In the Geneva Protocol of 1925 the international community banned the use of chemical and biological weapons. In 1973 and 1993 the prohibition was even strengthened by the Chemical Weapons Convention, which bans the development, production, stockpiling and transfer of these weapons. By now 193 states have ratified that treaty and the whole world expresses shock whenever it is violated, as in the Syrian civil war in 2017.(22)

Likewise, biological agents could be, and have sometimes been, used effectively in warfare. For example, in 1763 the British forces defending Fort Pitt, near Philadelphia, gave blankets from smallpox patients to Indian chiefs who had come to negotiate an end to their conflict.(23)

Epidemics of disease have been a regular feature of warfare throughout the ages. Indeed, more people died of “Spanish flu” during World War I — between 20 million and 50 million(24) — than were killed by military action. When troops move around, they may be exposed to pathogens and carry them with them. However, such epidemics are not spread intentionally, and there is not only a norm against the use of biological agents to kill enemies, but it is also prohibited by the same treaty that bans the use of chemical weapons.

Thus it is evident that at times even the most horrible technological means of killing — gunpowder, chemical, and biological weapons — have been banned and the prohibitions against them have generally been obeyed. People sometimes opt not to use weapons that are available to them. Take heart, for this proves that war is not inexorable.

Yet not all of the worst weapons have been banned, and until they are abolished, one cannot be as optimistic as Steven Pinker in expecting the end of warfare. There are four crucial initiatives going on now to ban weapons. If all are fulfilled, such optimism will be wholly justified. These propose to (a) regulate the trade in conventional arms among nations to prevent the violation of human rights; (b) ban the existence of nuclear weapons, and (c) prohibit the development of lethal autonomous weapons — those sometimes called “killer robots” — and (d) regulate the potential for cyberattacks. Our Platform for Survival promotes each of these bans in specific planks.

The Arms Trade Treaty

It is not now realistic to ban all firearms or other conventional weapons, if only because we depend on states to authorize the use of weapons by police to protect citizens whenever necessary. Nevertheless, it is possible to reduce the incidence and violence of contemporary wars by preventing the transfer of conventional weapons (e.g. assault rifles and other military hardware such as armored personnel carriers) to insurgent groups or lawless states.

Most of the real wars in today’s world differ from what we previously thought of as war. Mary Kaldor calls them “new wars.”(25) For centuries, war had meant conflicts between states with the maximum use of violence. But these “new wars” combine war, organized crime, and human rights violations. They are sometimes fought by global organizations, sometimes local ones; they are funded and organized sometimes by public agencies, sometimes private ones. They resort to such tactics as terrorism and destabilizing the enemy with false information on the Internet.

What is a suitable response to such wars, given our historical assumption that, according to Max Weber’s definitions, a sovereign state is any organization that succeeds in holding the exclusive right to use, threaten, or authorize physical force against residents of its territory.(26) In a time of globalization, Kaldor insists that the monopoly of legitimate organized violence must be shifted from a national to a transnational level and that international peacekeeping must be redefined as law enforcement of global norms. Kaldor’s proposal is consistent with our Platform for Survival’s plank 25, which promotes the cosmopolitan notion of “sustainable common security.”

This approach can begin with the development of a treaty regulating (though not completely banning) the international trade in conventional weapons. Such an international law — the Arms Trade Treaty — was adopted in 2013, when 155 UN member states voted in favor of it and three against, with 23 abstentions. It entered into force on 24 December 2014 after the fiftieth state ratified it.

The treaty, if well enforced, can reduce the incidence and violence of wars. Although one might suppose that the main source of weaponry for “new wars” is the black market trade in illegal arms, that is not the case. Until now, most violent movements have obtained their weapons by purchasing them openly from states that are indifferent as to whether or not the “end users” are responsible. The Arms Trade Treaty prohibits countries from permitting the transfer of weapons to any group or state that violates human rights or international humanitarian law. However, the treaty is only a regulation between states, having no bearing on nations’ internal gun laws.

The Nuclear Bomb: The “Perfect Weapon”?

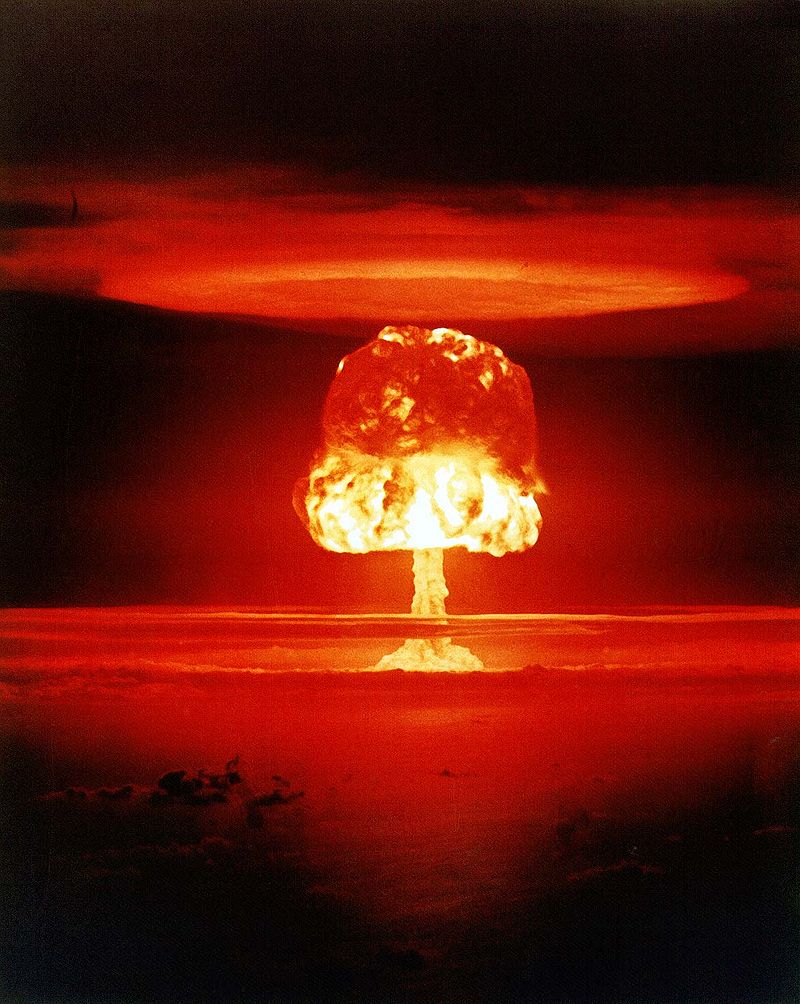

If there is such a thing as a “perfect sword,” or a “perfect storm,” then what would be a “perfect weapon”? Probably it would be a thermonuclear bomb. A nuclear bomb manifests precisely every attribute of an ideal killing machine; it is the consummate device for destroying enemies on an unlimited scale.

The largest hydrogen bomb that was ever exploded was the Soviet invention, Tsar Bomba, which was exploded by the Soviet Union on 30 October 1961 over Novaya Zemlya Island in the Russian Arctic Sea. It was equivalent to 58.6 megatons of TNT, and its fireball was five miles wide and could be seen from 630 miles away. It was ten times more powerful than all of the munitions expended during World War II combined. The blast wave orbited the earth three times. And even so, Tsar Bomba was only half the size that the inventors had originally planned to build. They had realized that exploding that a full-sized version might have been self-destructive. Indeed, such a weapon is too big ever to be used in a war. It is the “perfect weapon” — so good that it can kill everything, including its creators. No war with such weapons can ever be won. And, as Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan agreed, no nuclear war must ever be fought.

Tsar Bomba was only one bomb, and logically a single such perfect weapon ought to be enough — indeed, it should be “one too many.” You would want to dismantle it as soon as possible. But suppose your crazy enemy has such a bomb too. You might reasonably fear that, seeing you without one, he would take the opportunity to use his. To prevent that, you might want to keep some of these “perfect weapons” and declare that you will retaliate if he starts a fight.

That is what happened. The owners of nuclear weapons each kept a growing stockpile of them. Each side knew that any nuclear war would involve “mutual assured destruction” or “MAD” — the total annihilation of them all. Each side also knew that to explode one them in war would be an act of suicide, yet by 1986 there were 64,449 nuclear bombs on the planet.(27) Madness! But once such a situation of mutual deterrence is established, how can you end it?

The creators of “mutual assured destruction” proposed that the situation be reversed gradually by a process of “arm control.” The adversaries would meet, discuss their predicament, and agree to reduce their stockpiles in equal amounts, one step at a time. But this was tricky, for each side considered every weapon to be, not only a terrible threat, but also a necessity for “security.” It would be used only to deter the other side, keep the adversary from using his bomb.

But when your arsenals contain bombs of different sizes, in different types of delivery systems, it is hard to decide which combination of weapons to offer as your package, or what combination your adversary should offer to match yours. You could go on haggling over this kind of thing for decades.

As indeed the arms controllers have done. Negotiations for nuclear disarmament are supposed to take place by 55 states in Geneva — an organization called the Conference on Disarmament — “CD.” However, all decisions there require the unanimous consent of all parties— which never happens. No progress has been made at the “CD” since the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was negotiated in August 1996. In fact, the nuclear weapons states make it clear that they do not intend to relinquish their bombs within the foreseeable future, since they claim that their “security” depends upon retaining them.

In a strange sense, they are right. However weak a country may be, if it acquires a nuclear arsenal, any unfriendly country will think twice before threatening it. On the other hand, that is obviously an insane notion of “security.” The existence of a “perfect weapon” creates a logical paradox as well as a practical dilemma that no military leaders have solved.

The most humane solution to the paradox is one that the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev recognized and adopted in dealing with President Ronald Reagan during the Cold War. In this he was influenced by the German politician Egon Bahr, who explained in a 1994 interview:

“I came to a very astonishing result at that time. I thought, based on the mutual assured destruction, it’s quite obvious that neither side in a major nuclear exchange can win a war. So if this is true, then the result is in the political sphere — that the potential enemy becomes the partner of your own security and the other way around. In other words, despite the fact of the East-West conflict, both sides can live together or can die together. If this is true, we live in a period de facto of common security.

“And when I reached this result, I was surprised because this was against the experience of history. In history, when you fought, you had to beat the enemy. To become secure, you had to win a war. So, I wrote this down and I thought, better think it over.”(28)

This notion of common security became the guiding principle in the Palme Commission, which was then seeking solutions to the Cold War. The Russian participant in the Palme Commission, Georgy Arbatov, conveyed Bahr’s ideas to Mikhail Gorbachev, who was then the Soviet Minister of Agriculture. Evidently Gorbachev fully assimilated the notion to his own thinking. Shortly after he came to power, Egon Bahr met him and Gorbachev began explaining to him the idea of common security as if he had thought of it himself.(29)

Actually, however, Gorbachev’s notion of common security seems to have differed from that of Bahr, who believed that the situation of common security was created by, and even depended on, the existence of the relationship of mutual assured destruction. Gorbachev cannot have believed that, for it was he, more than anyone else, who sought to abolish all nuclear weapons for the sake of common security. And for about one day, October 11, 1986, in Reykjavik, Iceland he almost got his wish.

President Ronald Reagan shared Gorbachev’s recognition that nuclear war could never be won, and when the two men met in Iceland’s capital, Gorbachev offered to disarm every one of his nuclear weapons if the Americans would do the same with theirs. Since between them the two countries owned the vast majority of the world’s nuclear weapons, such a deal would have ended the arms race and moved humankind back closer to a state of genuine security.

Unfortunately, Ronald Reagan wanted to have both nuclear disarmament and a defence against nuclear weapons, lest any be kept and used to bomb the United States. He had developing a project called “Strategic Defense Initiative,” (then popularly called “Star Wars”) that he hoped would be able to intercept and destroy incoming nuclear missiles before they could reach their targets. If it worked, such a system would only be defensive; it could not attack an enemy but only defend against an enemy’s bombs. However, any country with such a “shield” would enjoy vast superiority over an enemy if it retained even a few nuclear weapons secretly, for its enemy would be helpless. Mutual Assured Destruction would no longer exist to confer its perverse version of “security” on both sides. Gorbachev realized that he could not trade away MAD for such partial progress. Thus the deal collapsed — much to the relief of Reagan’s advisers who had never wanted to give up their country’s nuclear arsenal at all. The subject was never officially broached again in the United States.

However, the conversation between the two superpower leaders did have benign effects. A year later the Soviet Union and the United States agreed to a new treaty, the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty of 1987. Both sides agreed to ban ground-launched missiles with a range between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. This removed the most frightening danger of that era, when both the Soviet side and the NATO side had been toe-to-toe, nearly installing weapons in Europe that would almost inevitably have led to a real nuclear war.

Indeed, Gorbachev went even further, removing Soviet troops from Eastern Europe and no longer promising to support any of the Communist regimes in that region, should their citizens wish to leave the Soviet sphere of influence — as indeed they did. In 1989, protests swept through those states and forced the Communist regimes, now lacking the support of Soviet military intervention, to relinquish power to formerly dissident political activists.

Nor was the Soviet Union itself exempt from opposition movements. In 1991 Gorbachev had to lower the Soviet flag from the Kremlin, for nationalism and the economic strains of transitioning to capitalism were fragmenting the union that he had led.

But the Cold War was over, and nuclear disarmament continued for several years, though relations between East and West never quite became cordial. Their last arms reduction agreement, the “New START” Treaty, was signed by Presidents Dmitri Medvedev and Barack Obama in 2010. Today there are still about 15,000 nuclear weapons on the planet, 90 percent of which belong to the US or Russia.(30) Moreover, to win approval of that treaty by the U.S. Senate, Obama had found it necessary to consent to modernizing the American nuclear arsenal, which is expected to cost about $1.5 trillion over the next thirty years—unless the Democrats now controlling the House of Representatives reverse that plan.

Tensions are still increasing, with Russia complaining that the US broke the promise it made to Gorbachev not to move NATO “one inch to the east” when he was so readily dismantling the Warsaw Treaty Organization. Indeed, he should probably have insisted that such a promise be recorded in a treaty, for most of the formerly Soviet bloc countries now hope to join NATO and several already have been admitted.

Moreover, although “Star Wars” never lived up to its promoters’ hopes, there is a continuing interest in defensive systems that can intercept incoming missiles in flight. NATO (read “the US”) is installing such a system called Aegis on ships in the Mediterranean, as well as ashore in Romania and Poland. Russia objects that these are not merely defensive, and in a recent paper Theodore A. Postol has shown that their objections are well founded. The canisters from which missiles can be launched in the Aegis Ashore system can easily have software installed that can launch cruise missiles, in violation of the INF Treaty.(31)

For its part, the US has accused Russia of violating the INF Treaty too by preparing to install a new missile that count hit Western European cities. Indeed, President Trump has announced his intention of withdrawing from the INF Treaty in six months and President Putin says he will develop new nuclear weaponry in response. We are in a new arms race.

Thus we see that the long experiment with arms control has failed to abolish nuclear weapons. What other options might succeed instead?

Though there is no prospect of speedy progress, the best alternative initiative is the “Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons” (TPNW), which was adopted (by a vote of 122 States in favour (with one vote against and one abstention) at the United Nations on 7 July 2017. It will enter into force 90 days after the fiftieth ratification has been deposited.(32)

The TPNW was the result, not of official arms control negotiations, but of action by civil society—notably an organization called the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). According to all international public opinion polls, the majority of citizens of virtually every country have always wanted nuclear weapons to be abolished, but they have lacked any means of forcing the nuclear weapons states to comply. But the governments of Norway, Mexico, and Austria convened several conferences that flatly denied that nuclear weapons can ever make the world safer. The participants reminded everyone of the catastrophic humanitarian effects of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and showed that on numerous occasions nuclear missiles have nearly been exploded, sometimes by intention, sometimes by mistake. ICAN’s argument has been convincing, and nations are ratifying the TPNW more quickly than with most previous treaties.

So far, the nuclear weapons states just ignore the treaty. Nevertheless, ICAN was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018 and continues pressing the nuclear states to comply, invoking shame to motivate them. To be sure, the leaders of all nuclear weapons states are shameless and are unmoved by humanitarian appeals to any ethical principles. On the other hand, they can no longer pretend to be progressing toward disarmament with the methods that they have used so far.

So the greatest threat lies ahead, when states are no longer inhibited by the INF treaty or, possibly, even by the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which may also be terminated if the nuclear arms race heats up. The US is making a new nuclear weapon only one-third the size of the Hiroshima bomb. One might consider such smaller bombs less dangerous than large ones, but that is not so. A small nuclear weapon is designed to be used in battle, not merely rattled ominously to intimidate or deter an enemy. We are in a post-MAD world now, and something new must be done to counter the threat.

Killer Robots and Cyberattacks

Gunpowder and nuclear weapons were “breakthroughs” in the development of weaponry. Now we must act quickly to prevent the development of other innovations with shocking potential: the application of artificial intelligence, robotics, and cyber-hacking to the development of weapons. Fortunately, we may still have enough time to stop lethal autonomous weapons, for the Pentagon is not yet working on producing them.(33) It is much harder to stop a weapons program after investors have sunk their savings into it and workers’ jobs would be lost by banning the weapon. Stopping cyberattacks will be harder to achieve, for there are already huge institutions using such systems.

In a way, it is entertaining to imagine two shiny robots fighting a duel — a nicer replay of the Iliad, when Achilles and Hector went mano-a-mano at Troy. If the two machines would merely kill each other we might even enjoy cheering for our side’s tin soldier, since no real blood would be shed. Unfortunately, lethal autonomous weapons will not be so restrained. Instead, they will be programmed to hunt down you or me–human adversaries. And if they have artificial intelligence, they may even learn to plan how to take over the world. Or at least such is the warning of some widely respected persons, including Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking.

But the Chinese rejected gunpowder, and we can reject killer robots and cyber war. The mechanism for opposing lethal autonomous weapons is a UN body that reviews and enforces a treaty called the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons. Of course, killer robots are not plausibly considered “conventional,” but they are officially categorized as such because they are not chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons. The common trait shared by all the banned so-called “conventional” weapons is that they are deemed “inhumane.” (Some of us do not consider any weapons humane except perhaps the darts that are used to tranquilize wild animals for medical treatment.) We must expect that lethal autonomous weapons, if allowed to select their own targets, would not be gentle, so there is an urgent need for such innovations to be prohibited.(34)

Cyberattacks are already a familiar experience for most of us, since we receive fraudulent phishing attacks or fake news in our social media all the time. Banks experience large losses through cyber theft, but prefer not to publicize that fact. There are even ransom attacks on civilians and hospitals, whereby the hacker promises to restore one’s computer to proper functioning only after receiving a large payoff. But these are mere annoyances when compared to an organized cyber war.

Indeed, a malevolent adversary can wreak terrible effects on any society today without firing any weapon. Already you are probably receiving “likes” on your Facebook account from foreign “bots” — fake accounts purporting to belong to someone who shares your values. The purpose is to lure you into reading posts that influence you to accept more extremist ideas or even to participate in extremist street demonstrations. We lack any easy means of identifying and intercepting these messages, though the political effects can indeed be significant in a democracy.

Still the effects of a violent cyber war can surpass these problems. It would be easy for the anti-ballistic missile defence system of any country or alliance to knock out the satellites belonging to its enemy. Already our electric grid and municipal water purification systems are vulnerable to attack, and we are entering the era of the “Internet of Things.” All our digital equipment— e.g. cars, door locks, kitchen stoves, phones — will be managed through remote systems that are vulnerable to hacking. If ten million electric cars stall at the same time on our streets, we will be helpless.

The plans to manage these threats are almost exclusively military: deter your enemy by proving that you can retaliate powerfully to any cyberattack. In 2010 the Obama Administration established a military Cyber Command in the military, and the US is not unique. Out of 114 states with some form of national cyber security programs, 47 assign some role to their armed forces.(35) Russia has already used cyberattacks against Estonia and Georgia; Israel has used them against Syria in conjunction with its bombing of a covert nuclear facility; and the US has used them (a cyber “worm” called “Stuxnet”) against Iran’s nuclear enrichment plant. None of these advanced countries seem genuinely interested in reaching an international agreement to regulate or ban any of their cyber activities.

On the other hand, there have been ostensible efforts to create limits. Obama’s administration called for some action and In 2011 China and Russia submitted a Code of Conduct for Information Security to the UN General Assembly. Most of the proposals in it were innocuous, but one clause asserted all states’ sovereign right to protect their ”information space”. The vagueness of this principle left others wondering whether the whole code of conduct was meant as a serious proposal or as only a cover for problematic intentions. There is an urgent need for international law to prevent cyber war.

Is Militarism the Main Problem?

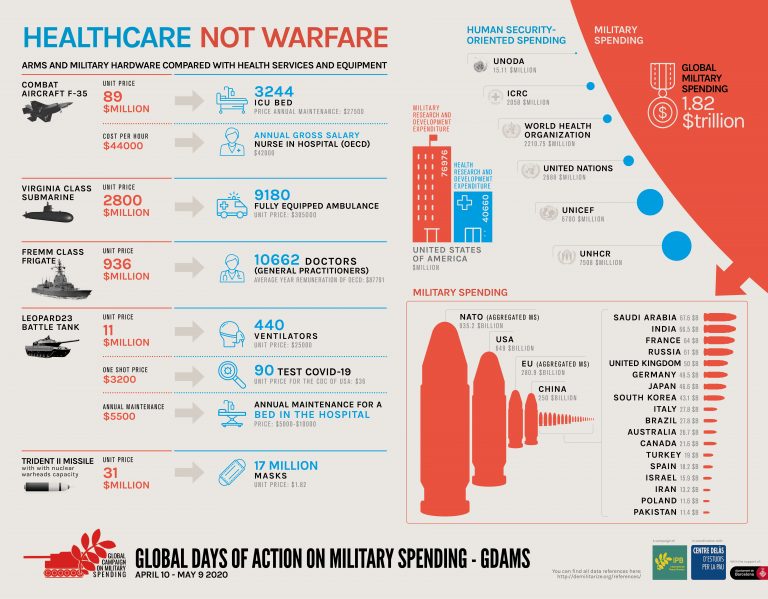

War and weapons constitute only one of the six global threats that we must urgently address, since any one of them could destroy civilization within a short interval. If we are to strategize and decide how to solve the six threats together, it may be useful to identify which option may have the largest payoff. Probably the answer is this: reduce militarism.

You may ask: Why militarism? Answer: Because war and weapons cause or exacerbate all five of the other global threats. By reducing the national armed forces (we probably cannot eliminate them entirely) we will reduce all the other risks.

Global warming is a danger on the same scale as war. To solve it we must urgently halt the emissions of greenhouse gas from every expendable human activity. And war is not only expendable, but abolishing it would benefit every person involved.

Moreover, it harms all the rest of us by emitting vast amounts of carbon. Manufacturing each gun, each airplane, each tank, each bomb, each bomb or bullet emits greenhouse gas. Flying the planes, shooting the bullets emits it too. The Pentagon is the largest consumer of fuel in the world. When it conducts a military operation overseas, such as in Afghanistan or Iraq, forty percent of the cost goes for transporting the fuel for use there. Then that fuel is used for injuring people and destroying buildings that later must be reconstructed, emitting even more carbon.

Suppose every country reduces its military by, say, 80 percent by the year 2030. No one can say with certainty how much this would reduce the CO2 in the planet’s atmosphere. However, one of the strongest arguments for cutting military expenditures is to limit climate change.

But militarism imposes huge opportunity costs. Diverting the money from militarism could enable other essential innovations, including limiting climate change. Global military expenditures between 1995 and 2016 hovered at about 2.3% of the world’s total Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The Sustainable Development Goals could be met with about half of that amount. In other words, such a shift in expenditures would enable humanity’s unmet needs to be provided, for health, education, agriculture and food security, access to modern energy, water supply and sanitation, telecommunications and transport infrastructure, ecosystems, and emergency response, humanitarian work, plus climate change mitigation and adaptation.(36)

The most grave threat besides the risk of nuclear war is climate change, and the most promising way of reducing CO2 in the air is by planting about a trillion trees. But that will cost vast sums. The only likely source of such funds is by diverting budgets from military activities to afforestation. Reducing militarism is the best — maybe the only realistic — way to reduce climate change. Unfortunately, in Kyoto and Paris accords, no country is even obliged to report /em> its military activities as part of its commitment to reduce CO2 emissions.

The other global threats are also all connected to militarism. For example, the only famines in the world today are not the result of food shortages. They are all created deliberately as acts of war or to subdue a population. For example, Saudi Arabia has blockaded food shipments into Yemen precisely to starve the Yemeni population into submission. And the people of Venezuela are starving because of their government’s deliberate policies to suppress protests against a military-backed regime. Famines are designed to violate human rights. Ending militarism would be a decisive step toward ending famine.

Likewise, ending militarism would reduce the incidence of epidemics. Historically, soldiers on the move carry diseases with them and spread them wherever they go. Germ warfare is prohibited by international law now but, as usual, more of the famine victims in Yemen are dying from diseases such as cholera than are actually starving to death or dying in battle. When people are weakened by stress and deprivation, they succumb to diseases. War is a cause.

Furthermore, ending militarism would reduce the risks of massive exposure to radioactivity. The original reason for creating reactors was to produce plutonium for nuclear bombs. Only later did anyone think of using the heat from these reactors as a means of generating electricity. Today large swathes of land are poisoned by radioactive waste, as for example around Hanford, Washington, where the Manhattan Project produced the radioactive ingredients for America’s nuclear arsenal. Seventy years later, the Hanford area is still poisonous and, as Ronan Farrow has reported, “Clean up of the toxic material at the Hanford Nuclear Site is expected to take 50 years.”(37) Numerous other contaminated military sites exist around the world, including battlefields in Syria and Iraq littered with depleted uranium(38) and a leaking dome-shaped dump in the Marshall Islands.(39)

There are countless ways of using radioactivity as a weapon of war. Crashing a plane into an enemy’s reactor may create a plume that would circle the planet, falling everywhere or polluting the oceans. Terrorist organizations are known to be seeking access to radioactive materials, probably for “dirty bombs” that will not explode but will contaminate large areas. The more radioactive waste there is in the world, the more opportunities will inevitably exist for these to become weapons. A solution to the problem requires two approaches: (a) managing the radioactive waste itself for many thousands of years, and (b) reducing the militarism that misuses these wastes as weapons. The technological challenge of burying the waste is probably easier than the social challenge of changing militaristic thinking.

Finally, reducing militarism obviously will reduce the risk of cyberattacks. Indeed, when we speak of cyberattacks, most people assume that we are speaking of a military attack, though there are probably more such attacks waged every day by civilian criminals stealing from businesses and individuals than are sponsored by foreign governments.

All six threats tend to interact causally, so that we need to address them together as a system. Nevertheless, there may be more “leverage” available by quickly demanding a reduction of militarism than through any other direct policy changes.

Still, this will not be easy. People have their jobs and their live savings tied up in the military-industrial complex and will not readily change to projects that can actually save the world. And they will argue that their security depends on having a robust military to defend their country from attack. Their concerns cannot properly be disregarded. If militarism is to be reduced, some other form of armed protection is necessary. We would not, for example, abolish the police in a country or city, for doing so always results in more crime and violence. A few countries (notably Costa Rica) have abolished their armed forces, but they still have police. Something similar must be provided at the international level. Two planks in the Platform for Survival call for the development of “sustainable common security” and a United Nations Emergency Peace Service, which would quickly rush to protect people anywhere in the world who are in danger of attack.

But how many people would trust the United Nations to protect them? There are surely good reasons for skepticism, since the Security Council is controlled ultimately by the veto power of five major states. Only a more democratically accountable body in the United Nations can be trusted to protect people equally, without regard to alliances and enmities between states. Hence, in the Enabling Measures section of the Platform for Survival, we consider some reforms of the United Nations that will make the United Nations a more reliable source of security.

All of these reforms, if introduced together, can reduce militarism and the risks that flow from war and weapons. This argues for a policy assigning top priority to the drastic, worldwide reduction of armed forces as the best means of saving the world from all six global threats.

Footnotes for this article can be seen at the Footnotes 1 page on this website (link will open in a new page).

Lethal Autonomous Weapons (LAWs) refers to future weapons that would select their targets and engage (kill) based on their programming. They will be “autonomous” in the sense that they would not require human intervention to actuate (act or operate according to its programming).(1) Being solely algorithmic driven, LAWs will be able to kill without any human interference or oversight.

Lethal Autonomous Weapons (LAWs) refers to future weapons that would select their targets and engage (kill) based on their programming. They will be “autonomous” in the sense that they would not require human intervention to actuate (act or operate according to its programming).(1) Being solely algorithmic driven, LAWs will be able to kill without any human interference or oversight.